[dropcap]A[/dropcap]t Monaco, the first significant race of the 1933 season, a new Grand Prix team made its debut: Scuderia CC, with Rudi Caracciola and Louis Chiron as its principals.

Two of the finest, most successful drivers in the world, they each had broken away from their established works teams. The Monagesque Chiron was forced out of Bugatti because of personal conflict. The German Caracciola was abandoned first by Mercedes, then Alfa Romeo, because of the economic doldrums that had swept the United States, then Europe. Supporting a Grand Prix team was simply too expensive. “You know,” Chiron said to his good friend Caracciola at the end of the previous season. “Why should we always win the prizes for other people? It would be much smarter to start our own firm.” Thus, “Scuderia CC” after their two initials, was born.

It was a time of fragmentation in motor sport. Teams often shuffled ranks or broke apart altogether. Top drivers–Caracciola, Chiron, Tazio Nuvolari, Achille Varzi, and Rene Dreyfus—did not know who they would be driving for next. Marque firms like Mercedes, who were synonymous with Grand Prix victory, ended their participation. Innovative racecar designs stalled, and officials couldn’t even settle on a definitive formula.

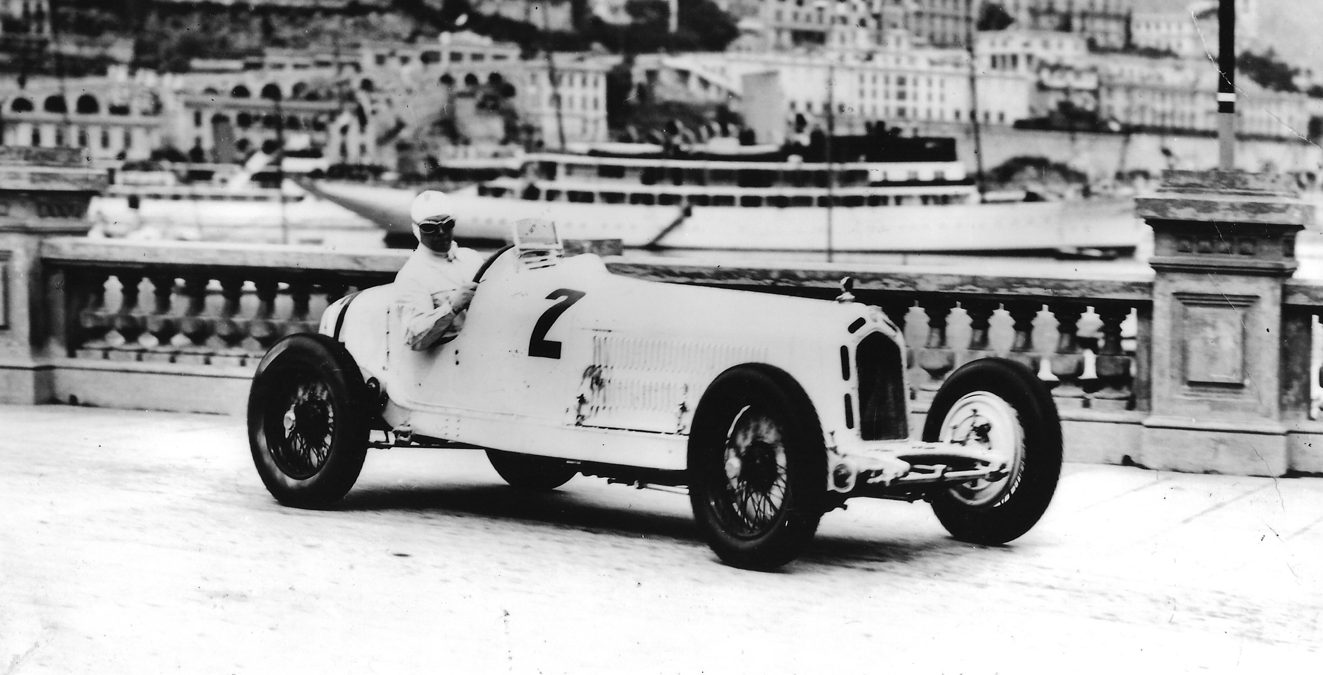

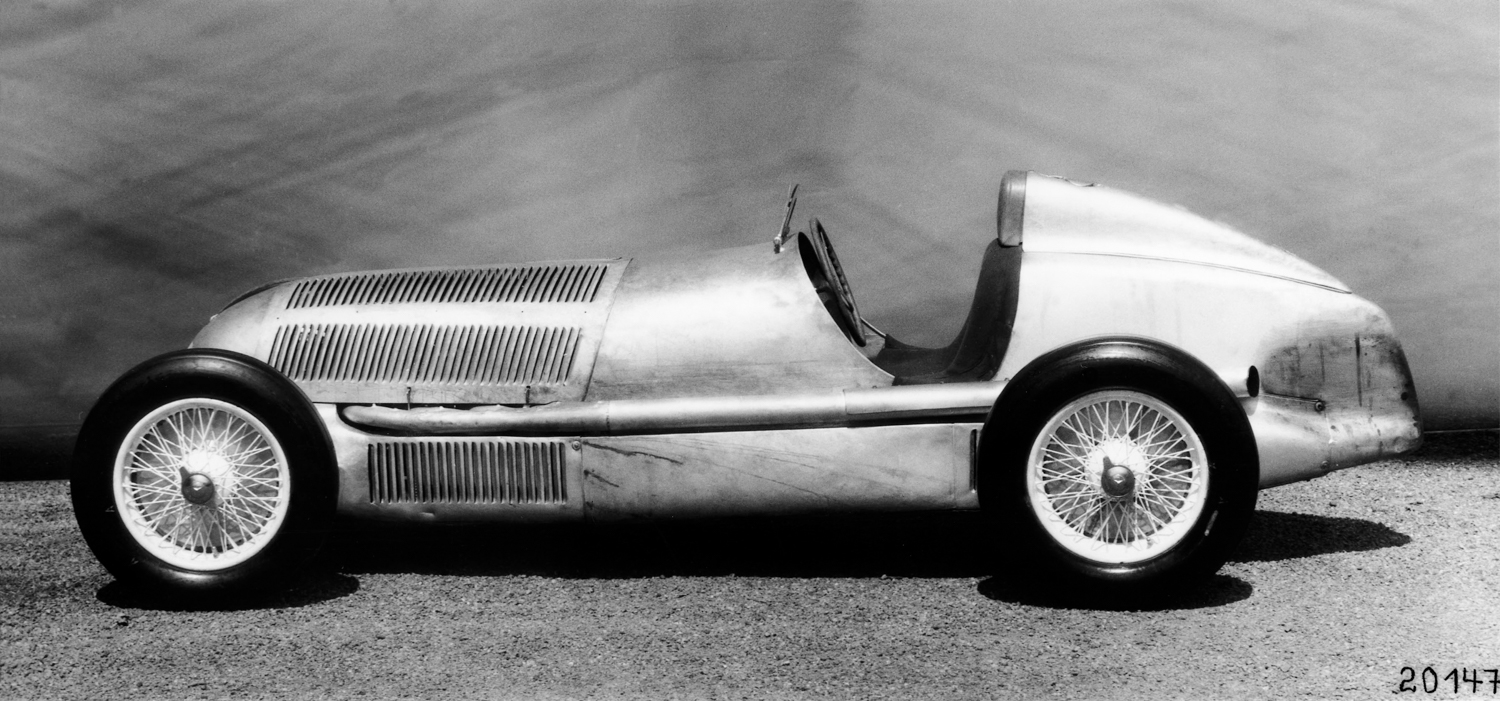

For the 1933 season, Scuderia CC had purchased a pair of 2.3-liter Alfa Romeo Monzas. A two-seater with a long tub-like hood and powered by a straight-8 supercharged engine, the racecars had earned their name with victory at the Italian Grand Prix victory two years before.

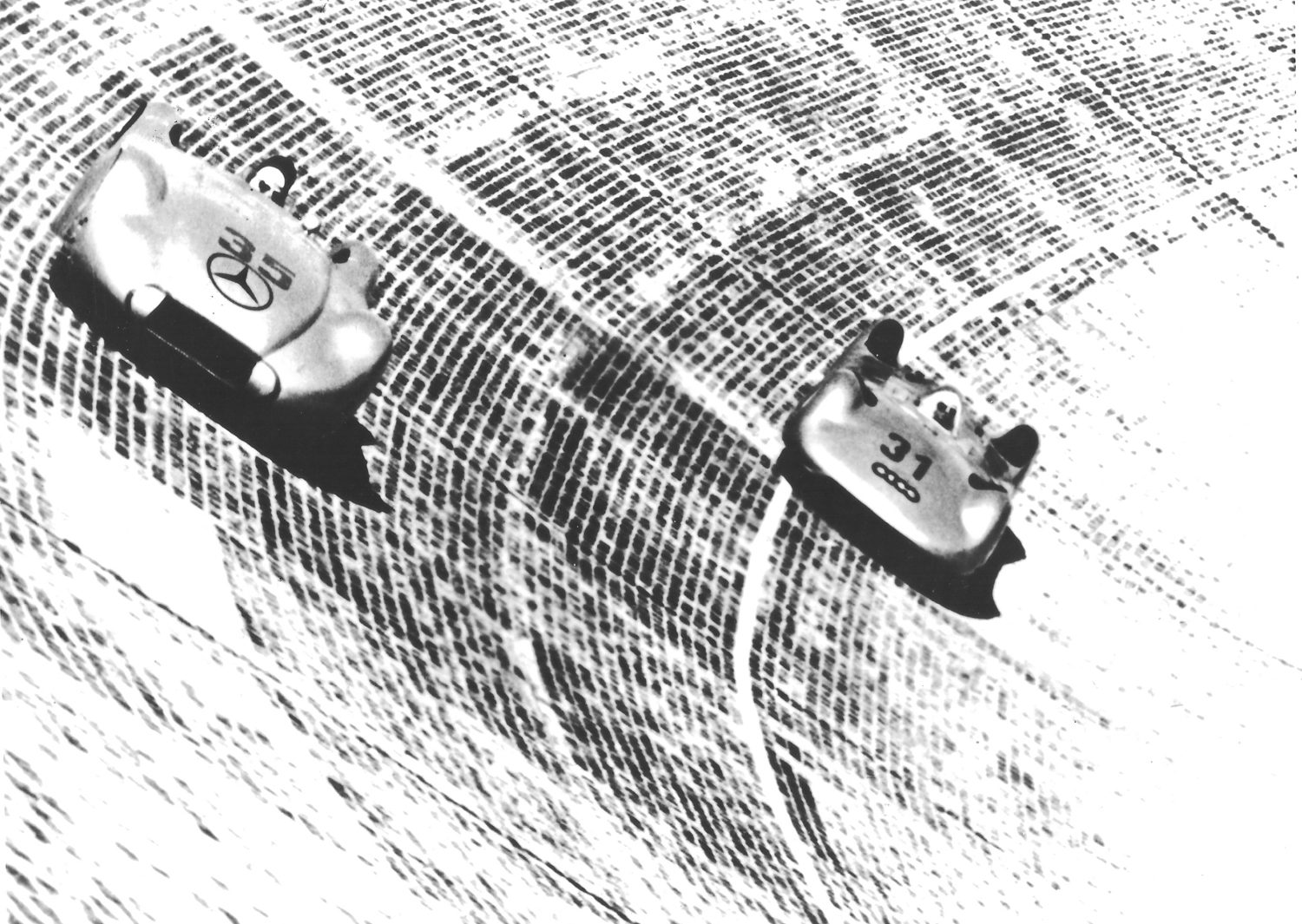

When Caracciola and Chiron showed up for practice at the Monaco Grand Prix, the signature red of their Alfa Romeos was gone. In a nod to their French-German partnership, Caracciola had his Monza painted white with a blue stripe running down its side. Chiron sported a blue Monza with a white stripe. Both cars carried the symbol of a pair of backward-facing Cs.

High hopes abounded for the newly formed team that Thursday, April 20. In a Grand Prix first, the starting grid on the day of the race would be determined by the best time achieved during the three days of practice. On the first day, Caracciola and Chiron focused more on testing out their Alfa Romeos than anything else. Chiron had never driven the make before, but under a sky pocked with black clouds, the two drivers managed to clock the fastest laps that morning: two minutes, three seconds. Nuvolari and his Italian archrival Varzi were one second slower. Frenchman René Dreyfus was off the pace by three seconds.

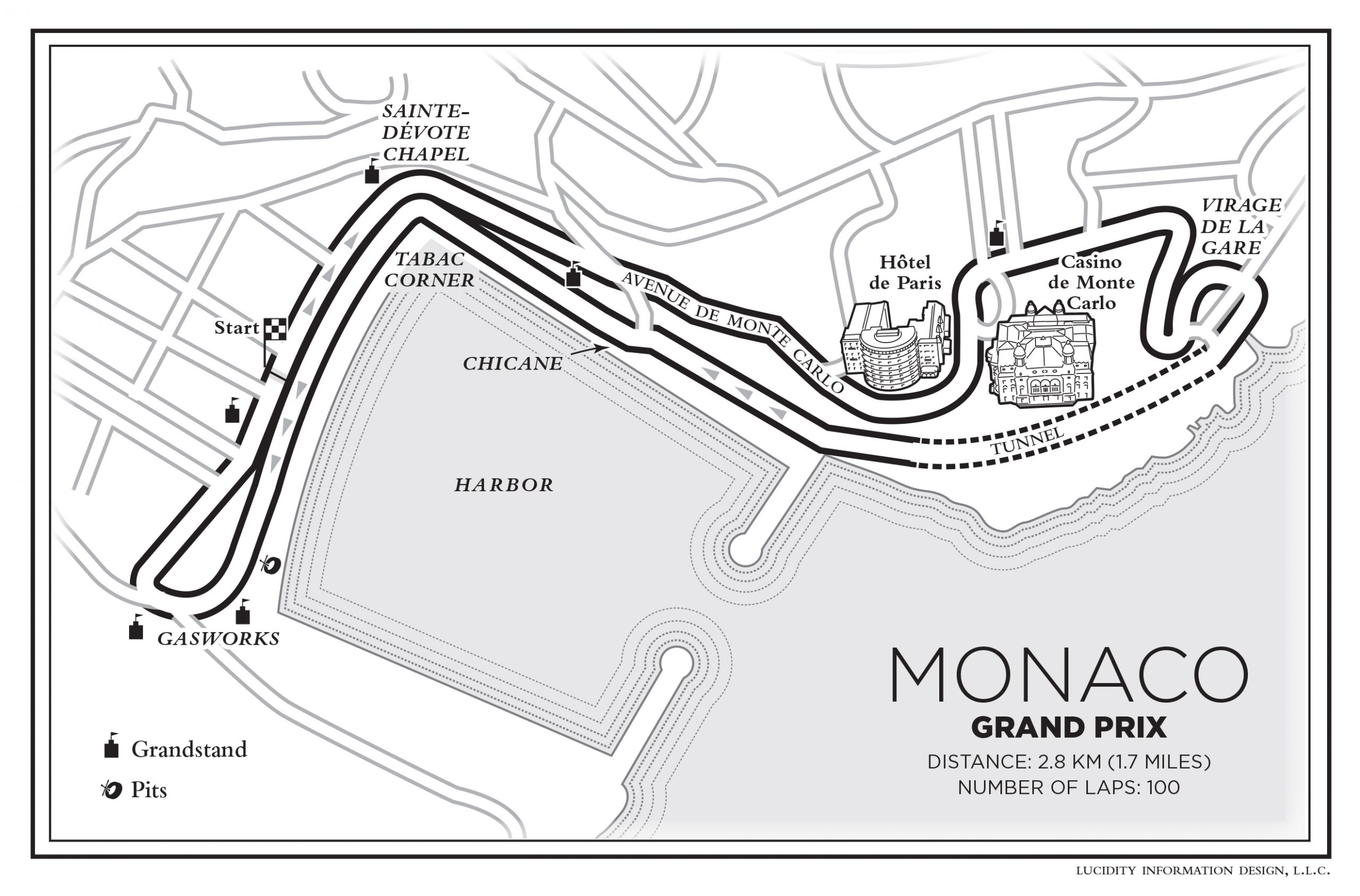

By their last run of the morning, the sky was clear, but a curtain of mist hung over the bay. Caracciola continued to lead down the corkscrew turns to the seafront, with Chiron on his tail. He was amazed at how quickly his teammate Chiron had gotten a feel for the Italian racecar. The two shot through the tunnel. Back in the sunlight, Caracciola zipped through the chicane, then accelerated down the straight toward the left-hand turn at Tabac Corner. A glance in his mirror showed Chiron nowhere in sight.

Caracciola braked slightly while looking in his rearview mirror to see where his teammate had gone. Suddenly, his Alfa went into a skid. Only one of the front brakes had engaged, he thought, as his car swept at 70 mph toward the stone parapet that separated the promenade from the sea.

Time slowed to a crawl. He cranked down through the gears. Calculating that he was more likely to survive a smash into Tabac Corner than a leap into the water, he steered away from the parapet. Hands tight on the wheel, he tried to regain control.

He was moving too fast.

His car snaked left, then right, on the road.

The stone steps came closer, and closer. At last Caracciola regained control, but it was too late. There was nothing to do.

The Alfa Romeo struck the wall first by the right wheel, then the whole side panel. The white metal body collapsed against the stone. Then the car propelled sideways for a few dozen feet before coming to a juddering stop.

Caracciola was stunned, but he thought he was okay. He did not feel the streams of blood coursing from his temple, nor realize that his thighbone was completely crushed. He wanted only to be free of the car that seemed to have molded itself around his body. With strength born of shock, he wrested himself out of his seat.

Several people were dashing down the steps from the upper road toward him. He was fine, Caracciola thought. No trouble here other than a wrecked car. Behind him there was a squealing stop. Chiron jumped out of his own Alfa.

Caracciola tried to take a step forward, and an explosion of pain overwhelmed him. His right leg gave out, and only Chiron’s arrival at his side kept him from collapsing onto the road.

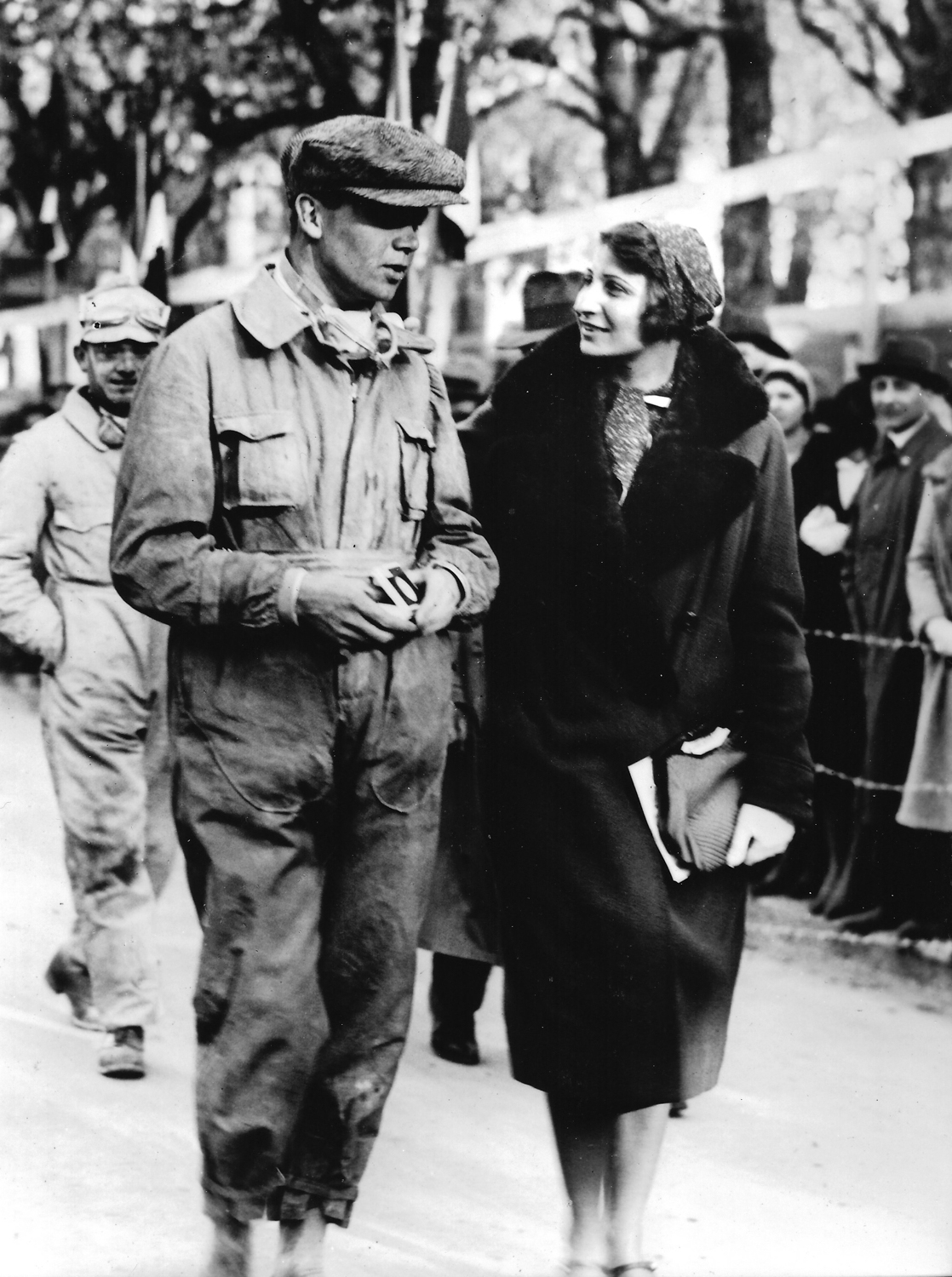

In the pits, Caracciola’s wife Charly and Chiron’s long-time girlfriend Alice “Baby” Hoffman waited for the two Alfas to finish their 25th lap. They should have come around by now. A shroud of worry that something terrible had happened fell over them.

Caracciola was carried away from the track in a simple wooden chair taken from a café. He sat upright in the chair in a state of shock. Blood ran into his eyes. The whine of racecars circling the track was deafening. Finally the ambulance arrived. Its crew placed Caracciola on a stretcher and jostled him inside. Each bump and turn through the streets of Monte Carlo sent ripples of pain through his leg. Something was very wrong with it. Caracciola dared not ask what.

At the hospital, he was carted first into the X-ray lab, then into the surgery ward. Waiting for the doctor, he stared through the high windows at the treetops waving in the wind. Everything in the room around him was sterile white and glass. The pain he had felt earlier was only a fraction of the agony that swallowed him now. His face was lacerated in several places, sweat beaded on his forehead, and the grim lock of his jaw spoke of his suffering.

Finally, a Dr. Trentini arrived. He was short and sallow-skinned. Caracciola disliked him instinctively. Neither spoke more than a few phrases in the other’s language, and they had trouble conversing. Caracciola just wanted him to get on with setting what was assuredly a broken leg. He wondered what was the delay.

Dr. Trentini and his assistant stood by the window, examining the X-rays, when Charly came into the room with Chiron and his girlfriend. “Tell them to pull my leg as hard as they can,” Caracciola urged. He had known other drivers to come out of such injuries with one leg shorter than another, which would have been unacceptable to him.

Dr. Trentini drew Charly from the room and raised the X-ray into the light. “Look, madame: The femur and the entire tibia bone are completely smashed. Your husband will never be able to drive again.”

Charly almost fainted. Baby did when her friend told her what the doctor had said.

Three days later, on Sunday afternoon, Caracciola was lying in his hospital bed, his right leg in an ill-shaped plaster cast up to the hip. Charly sat beside him, and flowers from well-wishers covered every available space. They were listening to a radio broadcast of the race, trying to decipher the commentary in French about the feverish contest between Nuvolari and Varzi.

In the final lap, near the finish, the engine of Nuvolari’s Alfa Romeo engine died and caught on fire. He leaped out and tried to push it toward the finish, enveloped in billowing black smoke. Driving a Bugatti, Varzi won easily, followed by Mario Borzacchini, with René Dreyfus in third. Louis Chiron was a distant fourth.

Despite everything, including the hurried consultation from an Italian specialist who had saved his leg from the saw, Caracciola was stunned that he had not recovered in time. He belonged in the race. That was his place in the world.

The plain fact was that his legs would never be a balanced pair again. He would have a permanent limp and was likely to only be able to take a few hobbled steps at a time. Racing looked like but a glory of the past.

Over the next five months, his leg bound in plaster, Caracciola recovered at the Rizzoli Orthopedic Institute, in Bologna, which was housed in an ancient hillside monastery south of the city. Its director, Dr. Vittorio Putti, was the preeminent Italian surgeon in his field.

Day after day, Caracciola spent most of his time in bed, playing cards with Charly or gazing out his window. Every time there was a race, he listened to it on the radio. Midseason, with Scuderia CC all but dead after the Monaco accident, Louis Chiron had joined the team started by Enzo Ferrari. Since Alfa Romeo had abandoned its own factory team, it had commissioned Scuderia Ferrari to field its cars. Piloting the monoposto P3 — emblazoned with the soon-to-be-famous prancing-horse badge — Chiron won the Spanish Grand Prix and two other races. Missing out on such an opportunity was torturous to Caracciola. He wanted nothing else but to drive again.

His progress remained unclear. After each inspection of Caracciola’s leg, Dr. Putti would only declare, “Well, it’ll be all right . . .”

At the end of September, Putti cut off Caracciola’s plaster cast, and two nurses rolled him into the X-ray lab. He hoped that the long struggle might soon be over, but Putti declared later that evening that more time in plaster would be needed. In late October, he removed this second cast. Caracciola attempted to walk on crutches, but the effort was too much. Further X-rays revealed that the cartilage in his right leg was healing improperly. Having made sure that Charly was in the room, Putti recommended surgery. Caracciola refused. He was convinced that he just needed to get back on his feet. The thought of more surgery and more months in plaster was intolerable.

“You won’t be able to drive anyhow!” Charly exclaimed. Her declaration stunned Caracciola. Since Monaco, nobody had dared say that his smashed thigh bone was career-ending. Although his right leg was now two inches shorter than his left, Caracciola was certain that he could overcome this challenge. When Putti advised that walking was likely ambition enough, Caracciola felt a coldness spread inside his body.

Charly tried to tell him that there were other things in life, that they could be happy without racing. He silenced her. “No surgery,” he told Putti. However, he consented to returning his leg to the plaster tomb on the condition that he could immediately leave the Institute.

They moved to a friend’s house in Lugano, Switzerland. Between periods of rest on the terrace overlooking the lake, Caracciola tried to spend more and more time on his feet. Despite using crutches, each swing of his leg sent a shot of pain through his hip. Charly walked beside him in case he stumbled.

In mid-November, his old friend Alfred Neubauer paid him a visit. Caracciola hid his plaster cast under loose trousers. The Mercedes team manager gave him a great hug, then they retired to the terrace. Caracciola sensed that his every move —and facial expression — was under inspection.

As always, Neubauer got straight to the point. Hitler was supporting Daimler-Benz in developing a new racecar for the 1934 season. Manfred Brauchitsch and Italian champion Luigi Fagioli had already signed on to the team. Neubauer wanted to know if Caracciola could drive again. They needed him.

“Of course, I can,” Caracciola said, before brazenly asking about the contract. Neubauer waved away the question. Caracciola needed to come to Stuttgart to discuss that — perhaps in January. The two then spent a pleasant afternoon together. Little was said about the car the company was developing, or about its sponsor, who had already firmed up his grip on absolute power. That was not their world, not their concern. They only hoped that support for Mercedes would continue.

After Neubauer returned to Germany, Caracciola learned through a friend that the team manager had reported to Daimler-Benz CEO Wilhelm Kissel that there was little chance Caracciola would compete again. Writing him off, they were looking for younger, fitter drivers.

Doctors removed the plaster cast in December. Every day, Caracciola tried to walk a little farther, cane in one hand, Charly holding the other. He was gathering strength, but his uneven legs made for an awkward gait, and the pain in his hip never faded.

In early January 1934, he and Charly traveled to Stuttgart to convince Kissel that he could drive again. Kissel was unmoved. Caracciola would have to show he was up to the task once they began training for the new season in early spring.

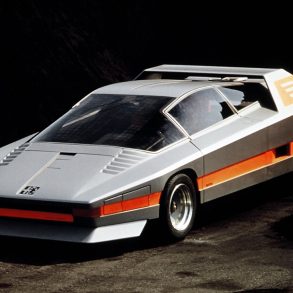

Neubauer brought him to the Untertürkheim plant to show him the new car. They passed a series of huge workshops and arrived at a small building surrounded by a high, barbed-wire fence. A guard checked their identification before allowing them through the gate. Everything about their work was top secret, Neubauer warned. Inside the workshop, Caracciola got his first look at the engine and the overall design of their latest Grand Prix car: the W25.

The prototype Mercedes engine, a supercharged 3.3-liter straight-eight, which Caracciola saw mounted on a dynamometer, was an absolute thoroughbred. Although not a revolutionary design, it benefited from ultraprecise construction and a host of improvements, allowing for horsepower measurements 50 percent greater than the Alfa P3.

Nibel matched the engine with a refined platform built of light alloys wherever possible. The W25 was a single-seater — new territory for Mercedes, as was its use of hydraulic brakes. It featured front- and rear-wheel independent suspension. They also advanced design by combining the gearbox and differential (which provided power from the crankshaft to the rear wheels) into a single unit. This provided better weight distribution and allowed the driver to sit lower in the cockpit. The W25 promised to ride balanced and tight to the ground. If everything was tuned correctly, it would be the fastest racecar to ever grace the Grand Prix.

Motivated more than ever to recover, Caracciola moved back to Arosa. During the bright winter days, he bathed his leg in sunshine. In the evenings, he ambled out for a walk with Charly, venturing farther each time. He accepted that he would never again move without pain. The real question was his ability to endure a 500-mile race in the tight W25 cockpit.

On February 2, Charly headed off for a day’s skiing with some friends. She was reluctant to go, but Caracciola convinced her that she deserved at least a day’s vacation after 10 months of nursing him. Later that afternoon, he hobbled down the snowbound hill to meet her at the train station. Neither she nor any of her ski companions showed up at the appointed hour. He returned home.

The sun set, and there continued to be no sign of Charly. Caracciola sat in the chalet, the lights out, the better to see her coming up the road. At 10:00 p.m., the guide who had led her tour approached the door. One look at him and Caracciola went white. Words followed: There had been an avalanche . . . Charly must have seen it; instead of dodging its approach, she looked to lean into its advance . . . her friends believed she might have had a heart attack; she was known to have a weak one, didn’t he know? . . . Charly was dead.

Without her and without racing, there was nothing left in his life.

In May, Caracciola fought through excruciating pain to drive the W25 and made the team. Only with the rise of the Mercedes Silver Arrows, brought about by the surge of nationalism in Grand Prix racing, would Rudi Caracciola return to greatness. In the process, he struck a devil’s bargain, becoming a figurehead for Hitler’s Third Reich as the world staggered toward the brink of war.

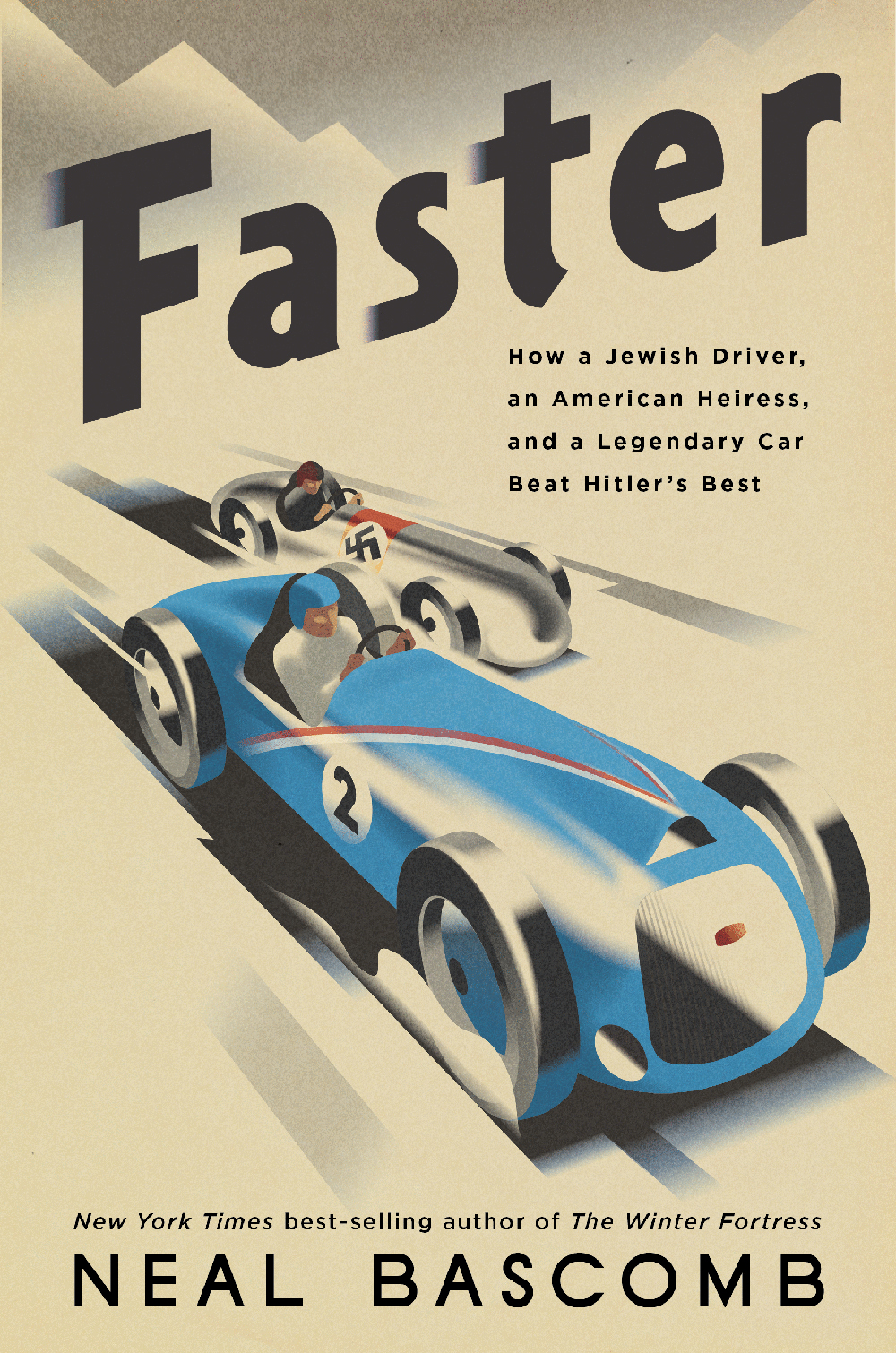

This feature is an excerpt from Neal Bascomb’s new book,

“FASTER: HOW A JEWISH DRIVER, AN AMERICAN HEIRESS, AND A LEGENDARY CAR BEAT HITLER’S BEST”

which is the pulse-pounding tale of triumph by the improbable team of Rene Dreyfus, Lucy Schell and Delahaye, over Hitler’s fearsome Silver Arrows during the golden age of auto racing.

For more information and to order visit nealbascomb.com