Cane and Abel

After retiring their Formula One program in 1962, Porsche refocused its efforts back to sports car racing. In 1963, work began on a new, dual-purpose road and racing sports car, the 904. In some respects an evolution of the RSK 718, the new 904 saw Porsche’s 2-liter, 4-cam, 4-cylinder engine mounted amidships in a ladder-style frame (a first for Porsche), with a bonded fiberglass body. Overall design of the new 904 fell to a young Ferdinand Alexander “Butzi” Porsche who, fresh out of school, worked on both the 904 and Porsche’s new roadcar, the 911.

It is at his juncture, in 1963, where we see that pivotal change occur at Porsche that would forever reshape the arc of the company and its racing prospects. Not long after Butzi Porsche joined the family business his cousin Ferdinand Piëch also joined Porsche. In order to understand the significance of this addition, one must first understand the Porsche family lineage. The company’s founder Ferdinand Porsche had two children, a son Ferdinand “Ferry” Porsche and a daughter Louise. Ferry Porsche would go on to have a son, unimaginatively also named Ferdinand (aka Butzi), while Louise would marry a wealthy Austrian attorney named Anton Piëch and—not wanting to be left out of the family naming convention—would also name their son, Ferdinand. As one might imagine considering the family history, the two young cousins spent a lot of their youth in and around the Porsche factory in Stuttgart. So, perhaps not surprisingly, by April of 1963, both of the “Cousins Ferdinand” where fresh out of school and working at Porsche—Butzi more on the design/styling side and Piëch on the engineering side. To say they were competitive is as much an understatement as saying Porsche built some racecars.

Hill Climbing

One of the areas where Porsche was focusing its sports car racing attention was European Hill Climbing. The European Hill Climb Championship was prestigious and afforded Porsche a great venue to showcase its engineering prowess. Porsche had dominated the Hill Climb Championship for many years until 1962, when Ferrari and Ludovico Scarfiotti snatched away the sports car title with Ferrari’s 2-liter, V6-powered 196 SP.

Over the subsequent two years, the new 904 did well to uphold Porsche’s mountain honors, but Ferrari was increasing its pressure on the Germans with its new V6-powered Dino sports racers. By 1965, it was clear Porsche was going to need something more, if it was going to retain its crown. At first the team at Porsche attempted to put an 8-cylinder engine—ostensibly sourced from the Formula One project—into a lighter weight, open-top “Berg Spyder” that utilized the existing 904 ladder-style chassis. However, the handling was poor and Ferrari’s Dino 206 SP regularly out ran it.

With Piëch now firmly at the reins of the R&D department (which, at the time, also encompassed racing car design), the decision was made in late July to rapidly build a completely new car, in the hopes of upstaging Ferrari’s Dino, at the upcoming Ollon-Villars Hill Climb—a mere four weeks away! Casting aside the 904’s ladder-style frame—and arguably the last vestige of Butzi’s imprint on the racing department—Piëch opted for a new, lightweight, tubular spaceframe chassis that featured a longer wheelbase and wider track that would result in a racecar weighing in at just 1170-lb, thanks to its fiberglass spyder bodywork, which would be bonded to the chassis for increased stiffness. Interestingly, Piëch and his team also wanted to go with lower profile 13-inch alloy wheels—like those used on the Dino and many Formula One cars of the time— but due to the limited amount of days before the race, they didn’t have time to make or custom order any. The solution was found at the German Grand Prix, on July 31, when Porsche bought a set of 13-in wheels, with uprights and suspension pieces from Colin Chapman and Lotus!

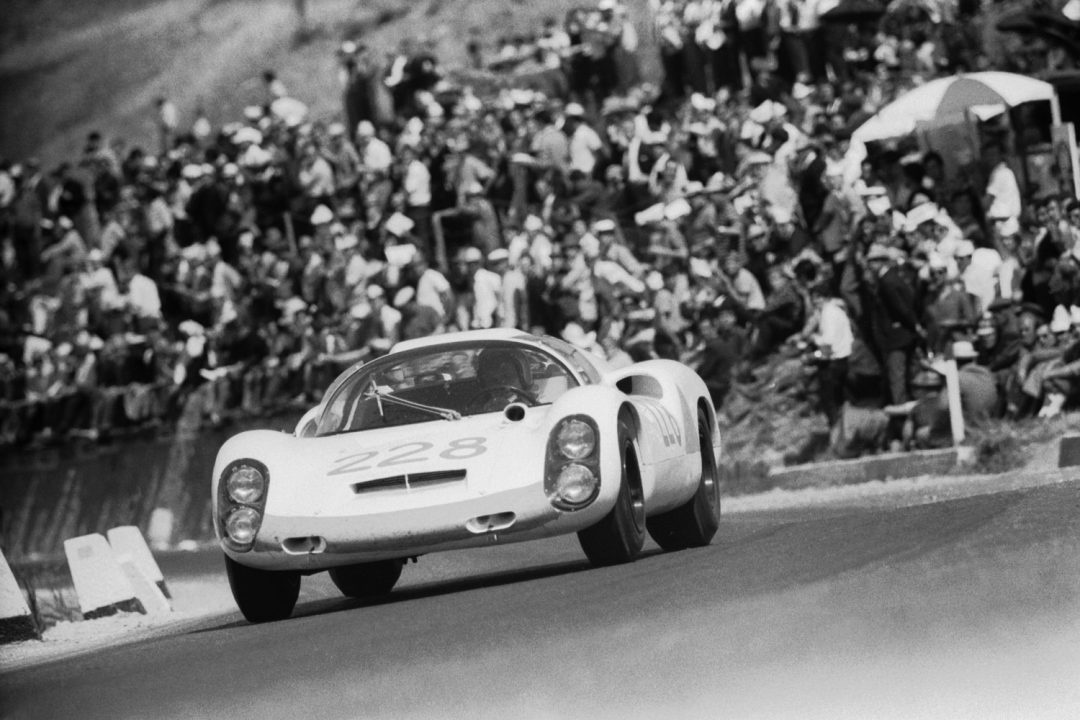

After a record 3-week thrash to design and construct the 240-hp, Flat-8 powered Ollon-Villars car, the new machine was taken to the Weissach test track on August 25, where it proved to be at least as good as the best iteration of the 904/8 Berg Spyder. While tire miscues hampered it at the Ollon-Villars race, resulting in Scarfiotti claiming the 1965 title, the Ollon-Villars car would go on to ultimately claim the 1966 championship, with Gerhard Mitter driving, but perhaps more importantly it would lay the ground work for an entirely new line of Porsche sports racers that would follow.

Enter the Carrera 6

Porsche’s early plans for the 1966 FIA Sports Car series had revolved around using the new Type 901, Flat-6 engine, developed for the 911, in the 904 chassis. A handful of these were built in 1965, but when the FIA lowered the homologation requirement for the 1966 season down to just 50 examples, Piëch saw an opportunity to compete with a more “purpose-built” sports racer, along the lines of the Ollon-Villars car. As such, the new 906 project would feature a tubular spaceframe evolution of the Ollon-Villars car, bodied as a coupe and mated to a Type 901/20 racing version of the 2-liter, Flat-6 capable of producing 210-hp at 8,000 rpm. Introduced as the Carrera 6 at the 1966 Daytona 24 Hours, the new 906 would rack up class victories at Daytona, Sebring, Monza, Spa and the Nürburgring, as well as an overall victory in that year’s punishing Targa Florio.

While the Carrera 6 was taking the FIA 2-liter prototype category by storm, the Ollon-Villars car (now designated 906-010 and updated into a coupe) was coming into its own on the 1966 Hill Climb Championship. Mitter racked up a series of wins at places like Rossfeld, Mont Ventoux and Trento-Bondone, before his car was upgraded with Bosch mechanical fuel injection, which Porsche had just started testing in endurance races that year. At Sestiére, Scarfiotti won, but for the July 31 hill climb at Freiburg, Porsche handed Mitter a new weapon.

Enter the 910

In the hopes of locking up the 1966 Hill Climb championship at Freiburg, Porsche unveiled a new iteration of the Ollon-Villars car for Mitter to drive. Designated the 910 (perhaps in homage to the Ollon-Villars’ #010 chassis number), this new sports racer was an evolution of the Ollon-Villars chassis, encompassing then-current work from the 906 as well. The new 910 retained the basic tubular spaceframe chassis layout of the Ollon-Villars car, but now with a shorter wheelbase (2,300-mm) and a wider front track (1,430-mm). Also carried over was the continued use of 13-inch wheels, though these were now cast magnesium and 8-in wide at the front and 9.5-in wide at the rear. However, new to this set up was the incorporation of a single, center-locking wheel nut, the first use of this now ubiquitous racing feature on any Porsche. For the suspension, Porsche redesigned the front and rear uneven wishbone, coilover suspensions with entirely new geometries such that the car could maintain negative camber even under the most extreme cornering forces. With this latest weapon, Mitter was able to best Scarfiotti at Freiburg and clinch the 1966 Hill Climb Championship for himself and Porsche.

As early as the summer of 1965, Piëch had firmly set his and Porsche’s sights on winning Le Mans outright and had consolidated all the racing car design under the aegis of a newly formed racing vehicle design department headed by Hans Mezger. Now there would be better continuity between race projects and the design team, which included famed engineer Helmuth Bott. As a result, progress proceeded at a breakneck pace with new designs coming to fruition even while their predecessors were still current and competitive.

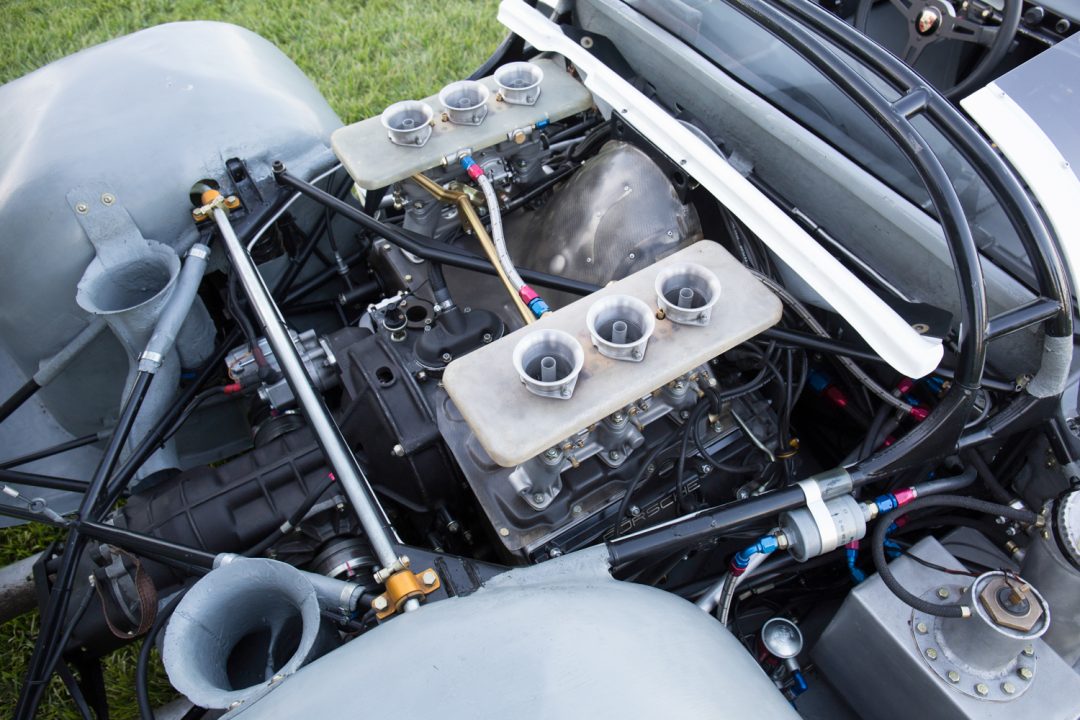

For the 1967 season, the plan was to race the 910 in hill climbing with the 2.0-liter Flat-8 engine, while the endurance events would see it compete with either the 2.0-liter Flat-6 engine, or the 2.2-liter Flat-8. Regardless of the category, each of these powerplants would utilize the newly developed Bosch mechanical fuel injection system, with dual transistorized ignition, and be mated to a Type 906 5-speed, all-synchromesh transaxle with limited slip differential. In the case of the 2.0-liter Type 901/21 endurance engines, these were now producing a reliable 220-hp, with an 8,200 rpm redline.

For the first race of the season, the 24 Hours of Daytona, Porsche entered only one 910 (chassis 003) for Hans Hermann and Jo Siffert. Racing against the much larger displacement Ferraris (330P4 and 412P), Ford GT40s and the Chaparrals, Hermann and Siffert qualified their little 2-liter car 17th on the grid, but outlasted most of the field to finish an impressive 4th overall (behind the three winning Ferraris) and 1st in the 2.0-liter class.

The 910s of Siffert/Hermann (#37) and Patrick/Miiter (#36) prepare for the start of the 1967 Sebring 12 Hours. Photo: Porsche

For the next race, the April 1, Sebring 12 Hours, Porsche entered two 910s for Siffert/Hermann (chassis 004, the car featured here) and Scooter Patrick/Gerhard Mitter (chassis 005). It is interesting to note that after a string of chassis failures in 1966, Piëch implemented a racing department edict of only entering new chassis in major international events. On the one hand, this insured that the factory endurance entries were always “fresh” cars, with less chance of stress related failures, and on the other hand they had to build 50 examples of the 910 to satisfy homologation requirements so it made sense to race a chassis once and then sell it on to a privateer to facilitate getting those cars out on the market.

This policy seemed to pay off as, much like Daytona, the Porsche team (910s and 906s) ran like freight trains at Sebring, quickly grinding out the hours with no interruptions other than refueling and driver changes. When the checkered flag fell, the 910s had outlasted all but two GT40s, with Mitter/Patrick finishing 3rd overall and 1st in class, and the Siffert/Hermann 910 finishing right behind in 4th overall and 2nd in class. In fact, had Siffert and Hermann not lost 10 minutes in the pits to change a headlamp after an on-track altercation, the positions would have been reversed.

The next race was the Monza 1000 Kms, on April 25, where new chassis 008 and 009 where entered for the teams of Rindt/Mitter and Siffert/Hermann respectively. Here too, the little 2.0-liter 910s outlasted the majority of the field, with the Rindt/Mitter 910 finishing 3rd overall behind two Ferrari 330P4s and 1st in class, while the Siffert/Hermann car, let a Ferrari 330 P4 slip between it and its teammates, resulting in them finishing 5th overall and 2nd in class.

The May 1st 1000 Kms at Spa saw another pair of 910s entered, chassis 007 for Siffert/Hermann and, unusually, the Sebring chassis 005 once more, this time for Koch/Mitter. Due to the short interval between Monza and Spa, only one factory Ferrari and no factory GT40s were entered. As a result, the clockwork-like 910s ran at the front with the Siffert/Hermann car finishing 2nd overall and 1st in class, only being bested by the Mirage M1 of Jacky Ickx and Dr. Dick Thompson. The Koch/Mitter 910 finished 7th overall and 2nd in class.

For the 1967 Targa Florio, held on May 14, Porsche waged an all-out war with no less than six 910s entered, three equipped with the 2.2-liter 8-cylinder engine, and three with the 2.0-liter 6-cylinder. Much to the dismay of the local tifosi, the 2.2-liter 910/8 (#024) of Paul Hawkins and Rolf Stommelen won overall, followed in second by the 2-liter 910/6 (#015) of Cella/Biscaldi, with the 910/6 (#014) of Elford/Neerpasch in third. The 910/6 of Siffert and Hermann (#012) would round out Porsche’s dominance of the top 10, in 6th place and 2nd in the sports car category.

Since many of the factory teams were now shifting their focus to June’s running of Le Mans, the May 28th running of the Nürburgring 1000 Kms saw a much smaller entry from the factory Ferrari and Ford teams, though Porsche once again threw in a 6-car entry with three 910/8s and three 910/6s. At the Ring, the effort was richly rewarded with Porsche winning its first major 1000 Kms overall victory. The 910/6 of Joe Buzzetta and Udo Shuetz (#007) claimed the overall win with the sister 910/6s of Hawkins/Koch (#013) and Elford/Neerpasch (#009) finishing second and third, followed by the 910/8 (#028) of Mitter/Bianchi.

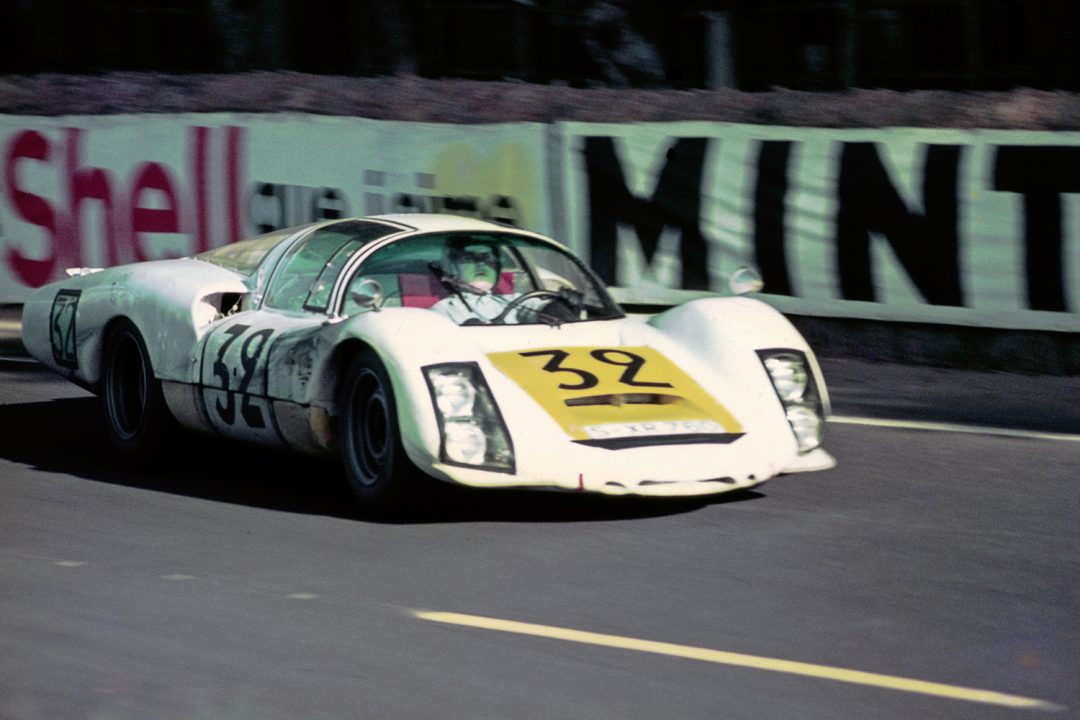

By the June running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Piëch and his crew had already built and tested the successor to the 906/910 line of sports racers, the 907. With overall victory at Le Mans now the goal, the focus was on the new, more aerodynamic 907, so only two 910/6s were entered to help shore up the Porsche effort. The Shuetz/Buzzetta entry (#017) retired after 84 laps with an uncharacteristic oil starvation problem, while the Stommelen/Neerpasch 910/6 (#016) would finish 6th overall and 2nd in class, one position behind its successor, the 907 of Siffert/Hermann. And with that, just as quickly as the 910 had burst onto the endurance racing scene just six months prior, it was essentially remaindered by the now relentless advance of Porsche’s development.

However, the 910 did see continued service that year as a factory entry, first in the Circuit of Mugello, a grueling 41-mile Tuscan road circuit, similar to the Targa Florio, where the 910/8s of Shuetz/Mitter and Neerpasch/Stommelen led home a resounding 1-2 victory after the Ferrari team withdrew due to the death of driver Guenther Klass during practice.

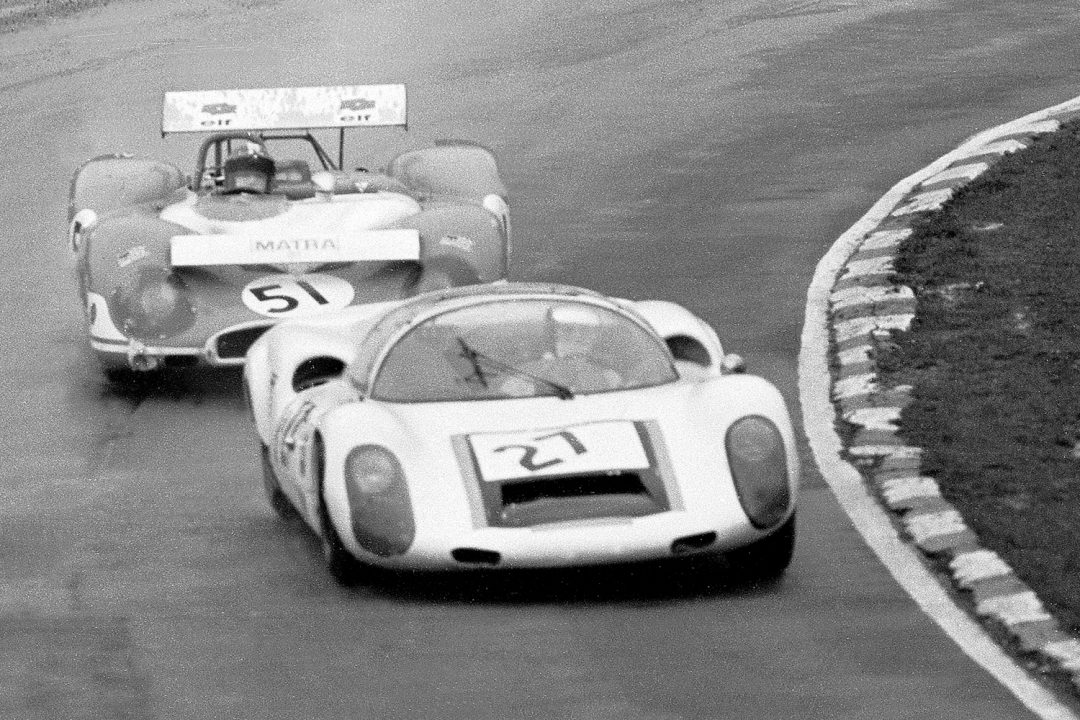

The last race of the season was the July 30th Brands Hatch 6 Hours and the stakes couldn’t have been higher as Ferrari and Porsche were tied for the overall Manufacturer’s Championship. As a result, Porsche brought one 907 and four 910s—a pair of 910/6s and a pair of 910/8s.

In the race, the Chaparral of Phil Hill and Mike Spence would eventually go on to win, but the real race was for second place with the Ferrari 330P4 of Chris Amon and Jackie Stewart in a tight battle with the 910/8 of Siffert and Bruce McLaren. As the final laps wound down, the Ferrari led the Porsche, but still needed to make a final stop for fuel—the result would decide which manufacturer won the FIA Manufacturers’ Championship. Amon dove into the pits, stayed in the cockpit and with a brief 26-second splash of fuel, he retuned to the track and was able to just keep ahead of the Porsche. At the flag, the Ferrari finished in second, the 910 in third and with that Ferrari won the championship…by just one point!

Second Life

While the 910 barely realized a full season as Porsche’s frontline sports racing car, before being surpassed by the 907, that is not to say that the 50 examples produced did not competitively continue on in races around the world. 910s continued to figure prominently in the hands of privateers for the subsequent two to three years, including a 9th place overall and first in class at Le Mans in 1969 (Poirot/Maublanc). In the case of our feature car, chassis #004, after being driven by Siffert and Hermann at Sebring in 1967, the car was sold to Spanish driver Alex Soler-Roig who drove it to a 2nd place at the Norisring, as well as several other top finishes in smaller German events that year. Soler-Roig raced the car only twice more in Germany, in 1968, before selling the car to Swiss racer Richard Broström. Conflicting records suggest Broström may have co-driven the 910 with Masten Gregory at Daytona, in 1969, finishing 11th overall, followed by a subsequent entry in that year’s Guards Trophy at Snetterton finishing in 6th. However, by August 1969, Broström appears to have sold the car to British racer Nick Gold who entered the car in the Guards Trophy at Brands Hatch that year, where he finished 5th.

Gold next entered the 910 (racing as car #27 in the above video) in the April 10, 1970 BOAC 1000 Kms at Brand Hatch with co-driver Mike Beuttler. Racing against the frontline 5-liter Ferrari 512s and Porsche 917s of the factories, the duo qualified their 3-year old, 2-liter 910 26th on the grid, but managed to finish 11th overall and 3rdin the 2.0-liter category.

Later that month, Gold drove the 910 one final time, at the Silverstone International, where he finished 12th. From there the 910, slipped off the racing world’s radar screen until re-emerging on the historic scene in the hands of such stalwarts as Reginald Howell and its most recent caretaker David Hagan.

Driving the 910

It’s not everyday that you can say that you got to test drive a Porsche 910 by chance. Yet, such was the case for me. I had flown up to Northern California’s Sonoma Raceway to test drive Shelby’s King Cobra Can-Am car. Under the care of Scott Drnek’s Virtuoso Performance, he and his crew were there testing a host of customer cars, of which the Shelby was one, and they couldn’t have been more helpful in insuring that the Shelby test drive went off without a hitch. After driving and photographing the Shelby, Drnek tilted his head toward a white and green Porsche parked in the garage and casually asked, “You want to drive that too?”

“Ah..yeah!’ was my response.

As luck would have it, the car in question turned out to be the Porsche 910 that Siffert and Hermann had raced at Sebring in 1967. Needless to say, I had my suit and helmet back on in record time, not wanting to give Scott any time to change his mind.

With the driver-side door flipped forward, it’s a very long stretch of the legs to step over the prodigious fiberglass threshold that covers the car’s side mounted fuel tanks. For a tall driver like myself, this was fairly easy as the 910 is currently configured to run with the roof panel removed, but were it in place it would require some impressive folding and gyrations to slide down into the nearly centrally mounted seat.

Once I’ve slipped down into the bucket seat I’m struck by the unusual layout of the interior. Bathed in a sea of beautifully gray-painted fiberglass, I become aware of a host of unusual angles: the wheel wells intrude pretty prominently into the cockpit, so your legs and feet have to angle a bit towards the pedals on the midline; the gauges are mounted on top of the low slung dash in two small binnacles angled to face the driver; and black-painted chassis tubes criss-cross the gray floorboard, generating a further series of angles. Yet, all that angularity found below the beltline is sharply contrasted by the presence of nothing but shapely curves above it. Looking out the heavily raked and re-curved windshield the driver’s field of vision is only broken by two large, graceful white curves delineating the placement of the 13” magnesium front wheels.

Considering this 910’s history and pedigree, it seems almost comical that one starts the car with a conventional key and lock on the dash! Turn the key, press down on the accelerator pedal slightly and the 910 bursts to life just as easily and trouble free as any garden-variety 911 roadcar. But blip that throttle and the sharp, growling exhaust note that assaults your eardrums informs you that while the basic design of the 2-liter Flat-6 engine may be related to that garden-variety 911, this is a purebred racing powerplant capable of boosting out 220 earsplitting horsepower.

With the car warmed up and ready to go, the next pleasant surprise was selecting first gear. Just an hour earlier, I had wrestled mightily with the ZF transaxle in the Shelby Can-Am car, but with the Porsche’s all-synchromesh 5-speed transaxle, first gear is easily snicked into place with no stirring or graunching. Pulling out into the pitlane, the 910 is quite content to happily growl along in first gear, without any of the surging or bucking one would experience with other purpose-built racecars. As I cruise my way to the track entrance, I have just a few seconds to fully take in my new surroundings. Nestled in the cockpit, the 910 provides the same sense of “wearing the racecar” that can also be found with any number of small formula cars. But while the formula cars provide more of a sense of being “in” the car, the 910 feels more like I’m wearing it “around” me. This sensation likely stems from the wide low cockpit, coupled with almost no roofline or “greenhouse “other than the heavily curved windshield.

However, these spatial musings quickly disappear as the 910 and I blend into the entrance to Turn 1 and I squeeze onto the gas pedal. BLAAAT…shift…BLAAT… powering up the left-hand dogleg to Turn 2, with a heavy throttle, the 910 releases one of the most glorious—and distinctive—engine notes. Not only is this engine note so distinctive and characteristic to 6-cylinder racing Porsches, but so is the acceleration, as 220 horsepower blast just 1254-lbs of tubes and plastic uphill towards the right-hand Turn 2.

Turn 2 is tricky because it is both off-camber and more or less blind. Earlier in the day, the Can-Am car required exquisite attention and deft handling here, whereas the 910 felt nimble, solid and remarkably light on its feet. Squeezing back on the throttle for the short run to Turn 3 provides another addictive dose of engine note and acceleration, before I make my way through the left-right Turn 3 & 3A complex. It is here that I’m struck by how neutral the 910’s handing is. Powering through these two turns, while quickly transferring the car’s weight from side to side, the 910 doesn’t provide even the remotest sense of polar moment of inertia—in fact, the car’s feeling of lightweight neutrality is almost a little unnerving!

After making my way on through Turns 4 and 5, I set up for another traditionally tricky part of the course, the long, off-camber, downhill Turn 6 sweeper that opens up onto the back straight. This is a fabulous place to over-cook it and take a potentially long and scary, backwards ride into the grass. But, yet again, the 910 was nothing but poised and confident as I accelerated my way out onto the backstretch.

Part of the track’s NHRA drag strip, the section between Turn 6 and Turn 7 is the longest straight on the track and I, of course, avail myself of the opportunity to launch the 910 up through the gears. With the all-synchromesh transmission, I confidently BLAAT my way up through the gears into fifth, before having to get hard on the brakes and work my way back down to second for the right-hand hairpin that is Turn 7. As one can imagine from a 1254-lb car engineered to race for 24 hours, the brakes are exceptionally good at hauling the 910 back down and, with not having to worry about double-clutching and matching rpms on the downshifts, less concentration is devoted to shifting, allowing more attention to be focused on late braking and turn-in. This, in itself, would be a huge “luxury” and advantage in a mentally draining, long distance race.

Turn 7 is tight, and almost a buttonhook, so here is where the 910 will most likely demonstrate any tendency to understeer. There is a little at initial turn-in (as it was designed to do), but just the slightest adjustment with the loud pedal, gently brings the rear end predictably right around to the optimal angle. As famed racer and Porsche expert Paul Frére noted when he tested the 910 for Autocar in period, “…the 910 is a very easy car to drive. It can be driven with real abandon, powersliding what is really a beautifully balanced and neutral steering car and keeping the tail under complete control by means of the precise and high-geared steering.”

My next challenge are the esses from the exit of Turn 7 through the final right-hand dogleg at Turn 8A. This is a long series of left-right-left turns that ideally are continuously accelerated through, with the last right at Turn 8A launching you towards a long expanse of K-rail(!) and another long bit of straight. This section requires rhythm, timing and precision, because if you miss the early apexes, you’ll be both late and too fast coming out of the last one, which can render a close encounter of the K-rail kind! This section—in my opinion, above all others at this track—provides the truest test of a car’s handling and balance. The 910 felt nothing but poised and stable as I powered my way from turn to turn. In fact, once out of Turn 8A and onto the back straight, I realized that I had significantly underestimated the 910’s capabilities here…however, being ever so aware of the privilege to sample Mr. Hagan’s piece of Porsche racing history, I remind myself not to get too confident or comfortable!

As I get a few more laps under my belt, I’m more and more struck by what an absolute delight the 910 is to drive. It’s fast, it’s easy to drive quickly and it makes the most glorious growl on the overrun!

While the 910 enjoyed one of the briefest stints as Porsche’s frontline sports racing car, its brief history should, in no way, diminish its significance in Porsche racing history. Not only did the 910 handily win the under 2-liter prototype championship in 1967, but it laid the true foundation for every Porsche endurance racer to follow, culminating in the triumphant 917. Along with that, the 910 was also emblematic of the complete change in the engineering and design culture at Porsche, brought about by Ferdinand Piëch, which not only elevated Porsche into an endurance racing powerhouse, but as a result, would also forever alter the arc of the company as a whole.

[button link=”https://sportscardigest.com//subscription-account/subscription-levels/” color=”green”]Want access to over 8,000 more articles and Photo Galleries like this? Click here to subscribe for as little as $3/month![/button]

SPECIFICATIONS

| Chassis | Steel tubular spaceframe |

| Wheelbase | 2300 mm |

| Track (Front) | 1430 mm |

| Track (Rear) | 1401 mm |

| Height | 980 mm |

| Weight | 1254 lb (575 Kg) |

| Engine | 1991-cc Flat-6 |

| Bore/Stroke | 80-mm x 66-mm |

| Compression | 10.3:1 |

| Induction | Bosch Mechanical Fuel Injection |

| Horsepower | 220 hp @ 8,000 rpm |

| Transmission | 5-speed transaxle w/ synchromesh |

| Wheels (Front) | 8 x 13 |

| Wheels (Rear) | 9.5 x 13 |

RESOURCES

Barth, Jurgen & Büsing, Gustav, The Porsche Book, David Bull Publishing, 2009.

Frére, Paul, The Racing Porsches, Arco Publishing, 1973.

Ludvigsen, Karl, Excellence Was Expected, Bentley Publishers, 2008.

Morgan, Peter, Porsche 917—The Winning Formula, Haynes, 1999.

Long, Brian, Porsche Racing Cars—1953-1975, Veloce Publishing, 2008.

Wimpffen, Janos, Time and Two Seats, Motorsport Research Group, 1999.

Casey…One of the best motorsport stories I’ve ever read. I was fortunate to have grown up in this epic era of spellbinding engineering and craftsmanship. I have been privileged to have met both Siffert and Hermann and your article brings all elements to life. You successfully captured the essence of these remarkable cars and the people immersed in their place in a storied history. Thank you for never letting amazing motorsport history fall by the wayside. Best regards, Mark Hoag

Many thanks, you’re too kind. This is such a wonderful car, with such fascinating history that these stories seem to write themselves. All the best, Casey